Minds matter in the Law: it matters whether misconduct is deliberate, knowing, mistaken, dishonest…

For example, for regulators, these issues may affect a range of matters:

- Whether to take informal/administrative/litigation routes

- Identifying potential breaches or contraventions

- Developing litigation strategies and prosecution briefs

- In considering settlement

- Assessing appropriate penalty/remedial outcomes

For discussion of the challenges to effective regulation posed by existing attribution rules, see Elise Bant, ‘Culpable Corporate Minds’ s’ (2021) UWA Law Review 352-388

How though do Courts traditionally identify corporate mental states?

Individualistic attribution rules, or Where’s Wally?

Traditionally, the law looks for the natural person whose mind counts for that of the corporation:

- ‘directing mind and will’ (Board of Directors, perhaps senior officers)

- the Meridian approach (asks whose mind counts for the purposes of this* statutory prohibition)

- More expansive statutory rules (eg Australian ‘Trade Practices Act’ model and equivalents, which deem the corporation to have the mindset of the person who engaged in the contravening conduct)

- Cf vicarious liability

These attribution rules are no longer ‘fit for purpose’ in the modern corporate context.

Image credit: Where’s Wally by Martin Handford, via www.seekpng.com

Vicarious Liability

Vicarious liability is a slippery concept. It arguably captures three different ideas:

- Vicarious conduct (where a person acts through another, and is directly responsible for those actions: eg an agent)

- Vicarious liability (where a person is responsible for the wrongdoing of another – an indirect or derivative form of liability) and

- Non-delegable duty (where a person has a duty to ensure that, for example, another person takes reasonable care)

For explanation and discussion, see the joint judgment of Edelman and Steward JJ in CCIG Investments Pty Ltd v Schokman [2023] HCA 21

The Modern Corporate Context

- Corporations are ‘artificial’ persons

- They have no ‘natural’ brain

- Massive, multinational corporations have devolved structures and numerous teams, departments, agents, associated corporate groups and networks…

- Information silos are commonplace

- The human actors through which a corporation commonly acts change, leave, get promoted, die…

- Corporations are more than the sum of their parts!

- That is even before we start thinking about the problems of automated and algorithmic processes

Law Reform Commissions in Australia and England agree that traditional approaches make the task of holding corporations responsible for serious misconduct hugely complex, expensive and often impossible.

Are there alternative models?

Where’s WALL-E?

Where automated and algorithmic processes carry out corporate conduct, there may be very limited individual involvement. On traditional ‘Where’s Wally’ attribution rules , this provides a perfect corporate escape-route. The narrative becomes…

- ‘System errors’

- The ‘black box’

- The computer/ robot/AI made me do it!

For full discussion, see Elise Bant, ‘Where’s WALL-E? Corporate Fraud in the Digital Age’ in H Tijo and PS Davies (eds) Fraud and Risk in Commercial Law (Hart Publishing, Oxford)

Image credit: WALL-E robot toy character from computer-animated science fiction film produced by Pixar Animation Studios, via zhitkov – stock.adobe.com

Alternative models

Some attribution models try to take different approaches:

For explanation of how Professor Bant’s new model of Systems Intentionality relates to these other models, and its advantages, see Elise Bant and Rebecca Faugno, ‘Corporate Culture and Systems Intentionality: Part of the Regulator’s Essential Toolkit’ (2024) Journal of Corporate Law Studies 345

Aggregation

This model ‘aggregates’ the states of mind of individuals within a corporation, to assess its overall, cumulative consciousness.

It is a pragmatic response to information barriers and ‘diffused’ knowledge within companies. If two or more people within a company know something, the company knows it!

But there are problems:

- How does it work to identify other mental states, like intention and mistake? Whose mind counts, and why?

- If corporations are more than the sum of their parts, aggregating individuals’ mindsets does not really make sense….

See discussion in Elise Bant, Corporate Mistake in Jodi Gardner et al. (eds), Politics, Policy and Private Law Vol II (Hart Publishing, 2024)

Aggregation in Australia

Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Kojic [2016] FCAFC 186 [112] (Edelman J)

It is not easy to see how a corporation, which can only act through natural persons, can engage in unconscionable conduct when none of those natural persons acts unconscionably. Similar reasoning has led courts to reject submissions that a corporation has acted fraudulently where no individual has done so (in instances of deceit) and that a corporation has acted contumeliously where no individual has done so (in cases of exemplary damages).

But, at [153], Edelman J further notes:

…it might be difficult for a corporation to avoid a finding that it has acted unconscionably if it puts into place procedures intended to ensure that no particular individual could have the requisite knowledge. [emphasis added]

How might this connect to Systems Intentionality? See Elise Bant and Jeannie Marie Paterson, ‘Systems of Misconduct: Corporate Culpability and Statutory Unconscionability’ (2021) 15 Journal of Equity 63-91

Corporate Culture

Criminal Code Act 1995 section 12 (3)

- Provides that corporate intention, knowledge or recklessness can be demonstrated where a corporate culture ‘directed, encouraged tolerated or led’ to misconduct

- Corporate Culture = ‘an attitude, policy, rule, course of conduct or practice’.

This concept is hugely influential as a regulatory tool in Australia: eg

- ASX guidelines Principle 3: ‘culture of acting lawfully, ethically and responsibly’

- Explicit civil and criminal pecuniary penalty consideration

- At the heart of recent banking and casino royal commissions.

But it has not been successful as a liability mechanism – too uncertain!

See Elise Bant,’ The Culpable Corporate Mind‘, (2021) 48 UWA Law Review 352-388

Failure to Prevent (FTP) Offences

UK FTP offences generally have two limbs:

- Commission (but not necessarily conviction) of a predicate offence by an associate of the defendant company

- Onus then falls on defendant company to show that it had ‘reasonable precautions’ or ‘adequate procedures’ in place

Benefits:

- Seem to avoid problem of attribution entirely

- Reflect genuine (but lesser) organisational blameworthiness (a ‘failure’ to prevent someone else’s more serious misconduct)

- Work in practice!

Now introduced into Australia: Crimes Legislation Amendment (Combatting Foreign Bribery) Act 2024

But as the Rolls-Royce Bribery Scandal shows, they have limitations.

Rolls-Royce and FTP bribery:

- RR’s corrupt bribery practices were ‘endemic’ across multiple jurisdictions and years.

- Where an individual employee engaged in bribery resigned ‘this did not lead to any change in approach from the remaining employees’.

- Judge characterised RR as being in ‘wilful disregard’ of the offending conduct in one case.

- One corrupt dealing was framed in terms of an ‘organised and considered scheme’.

- In some cases, directors or senior officers were not directly implicated. Should that make a difference to RR’s overall, corporate blameworthiness?

- Was this a culpable ‘failure to prevent’ – or the company’s own business model? Does it matter?

For a Systems Intentionality analysis, see Elise Bant and Rebecca Faugno, ‘Corporate Culture and Systems Intentionality: Part of the Regulator’s Essential Toolkit’ (2024) Journal of Corporate Law Studies 345

Systems Intentionality

‘Corporations manifest their state of mind through their systems of conduct, policies and practices.’

- A ‘system of conduct’ is a plan of procedure, or internal method, a coordinated step of steps directed to some end

- A ‘practice’ may develop organically, commonly involving habitual or ‘customary’ patterns of behaviour

- A ‘policy’ operates at a higher level of generality, manifesting overarching purposes, beliefs and values. Policies are analogous to ‘Corporate Culture‘

How do we identify a ‘system of conduct’?

How do systems of conduct manifest mental states?

Click here for law reform proposals to introduce Systems Intentionality.

Click here for further implications of the model, including for corporate governance.

Click here for news of High Court endorsement of Systems Intentionality.

Systems Intentionality

‘Corporations manifest their states of mind through their systems of conduct, policies and practices.’

- A corporation’s system of conduct both reveals the corporate intention and embodies or instantiates that intention. Ie corporations think through their systems – and so, assessment and characterisation of the system enables us to know the corporate state of mind.

- Systems are inherently purposive: they co-ordinate and connect steps and processes to some end

- Knowledge of certain matters will be implicit in the system: eg a predatory business model that will only be profitable if a certain class of vulnerable consumers exists and is successfully exploited (ASIC v National Exchange).

Click here for a detailed explanation of how Systems Intentionality reveals corporate mental states.

Click here and here for detailed analysis of how Systems Intentionality reveals corporate mental states in automated and algorithmic contexts.

Evidence of the (real) systems

Internal:

- Employee testimony (including whistleblowers)

- Internal ‘scripts’, training-as-delivered

- Remuneration/reward/promotion criteria

- Complaint processes and scripts

- Default settings on automated programs

- Audit outcomes…

External:

- Patterns of harm/commonality between victims

- Communications (including on complaints)

- Incentives and disincentives provided to target market

- User experience of website

- Email and chat exchanges

- Audit outcomes…

Click here for detailed discussion.

Lessons for Corporate Governance and Regulation from Systems Intentionality

- ‘Heads on sticks’ aren’t enough!

- Root cause(s) analysis is required, including the contributing ‘structures, values and practices’

- Also develop, test, embed, audit and remediate systemic reform plan

- Role of ethical and compliant practices in leaders and employees embedded in these systems

- Oversight mechanism(s) – regulators

- It all takes time and resources… (Rolls-Royce, Crown)

Sample Scenarios

Systems Intentionality has been modelled extensively on real-life scenarios:

- ‘Fees for no services’

- Crown Casino’s ‘anti-money laundering’ and ‘responsible gambling’ failures

- Westpac’s (not so) ‘super’ strategy

- NAB’s ‘Introducer’ program

- ASIC v National Exchange

- Asset-based lending

- Stubbings v Jams 2

- Pain(ful)-relief

- ‘Choice Architecture’ in website design

- Subscription (mal)practices

- Artificial intelligence systems

Example 1: Fees for no services

- Life insurance fees and fees for financial advice are charged through automated fee deduction systems

- The default settings are to deduct fees on an ongoing basis (‘choice architecture’)

- Given the nature of the products (life insurance and financial advice), it is inevitable that the conditions justifying fees will change

- There are no, or no functioning, adjustment, monitoring or corrective mechanisms.

‘Systems error’, incompetence, or deliberate and dishonest conduct? Click here for a Systems Intentionality analysis.

Example 2: Crown Casino

- Millions of dollars were ‘laundered’ through Crown accounts.

- Directors of Crown didn’t know the particular accounts existed.

- Low-level ‘cage’ staff had a ‘practice’ of aggregating payments to the accounts

- AML team were entirely separate and unaware of the practice

- No audits, no communication

- Banks’ repeated warnings about this were never reported to the directors.

Errors and incompetence? Click here for the Systems Intentionality analysis.

Example 3: Crown Casino II

- Marketing strategy to bus elderly members of community groups to casino for day of fun.

- Various incentives to sign up (buffet, free bus, vouchers)

- For community groups to receive Crown subsidy, participants had to stay for 4-6 hours.

- No reported audit/checking of consequences, and programme ran for 20 years.

- Independent studies suggested litany of gambling-related harms resulted.

- Crown had a beautiful ‘responsible gambling’ policy on its website throughout.

Just bad judgement? Click here for a Systems Intentionality analysis.

Example 4: Westpac’s (not so) super

- Westpac had a ‘campaign’ to get bank/super customers to roll over their funds into the Westpac group super accounts, to increase funds under management

- Team members were trained in a prescribed marketing and sales technique that was ‘inherently likely’ to give rise to a range of prohibited conduct (in particular, personal financial advice)

- Part of the strategy was to induce an ‘erroneous assumption’ in the minds of its customers that the decision to consolidate was straightforward – a ‘win-win’ from Westpac’s business perspective.

What did Westpac know? What was the relevance of perfect, formal compliance policies? What evidence was relevant, and why? Click here for a Systems Intentionality analysis.

Example 5: NAB’s ‘Introducer’ program

- Unlicensed ‘Introducers ’ would ‘ spot ’ prospective customers and ‘ refer ’ them to bankers; if the bank then advanced a loan, the Introducers were rewarded by commission – the bigger the loan, the bigger the reward

- NAB provided no training, oversight, audits, or ramifications for misconduct.

- Widespread Introducer misconduct included forgery, inclusion of false information in loan application documents and conflicts of interest

- NAB’s formal compliance policies were routinely honoured in the breach

- Program was hugely profitable for NAB, and continued for nearly 20 years before whistleblowers spoke out.

Click here for a Systems Intentionality analysis.

Example 6: ASIC v National Exchange [2005] FCAFC 226

- National Exchange sent unsolicited off-market offers to members of a demutualised company, Aevum Ltd.

- The offer price was at a substantial undervalue of their true worth.

- A correct range of values for the shares was disclosed on the reverse side of the offer document.

- 257 shareholders accepted the offer.

Through the lens of SI, objectively speaking, the business model was inherently predatory in design. It could only work (be profitable) if there existed a vulnerable class of sellers, (older, inexperienced and commercially irrational) that would fall for the low-ball offer.

- Corporate knowledge of that vulnerability was implicit in the system of conduct. Click here and here for discussion.

- Compare Stubbings v Jams 2 . Click here for a full analysis of predatory business models.

Example 7: Asset-based lending

Suppose this business model:

- ‘Unbankable’ consumer borrowers (with no income) are told to set up a company to borrow for business purposes

- They become personal guarantors and put up their residential property as security

- All dealings are done through professional intermediaries (introducers, solicitors, accountants) who provide pro forma ‘certificates of independent advice’… These intermediaries earn exorbitant fees for their services.

- Information silos are built into the business model, so Lender does not ‘know’ anything and never deals with the consumers.

- The consumers are doomed to fail and lose everything.

Click here for the High Court’s treatment of this scenario in Stubbings v Jams 2. How similar is it to the Systems Intentionality model?

Example 8: Stubbings v Jams 2 [2022] HCA 6

On the business model:

- Kiefel CJ, Keane and Gleeson JJ: the ‘deployment of such artifices’ where a lender or its agent deliberately distances itself from evidence confirming the dangerous nature of the transaction for the borrower or its guarantor is ‘evidence pointing to an exploitative state of mind on the part of the lender’.

- Gordon J: A certain level of lender knowledge of special disadvantage was implicit in the ‘system of conduct’, and the system was actively designed to immunise lender from further, actual knowledge.

- Steward J: the system of conduct was an ‘artifice designed to prevent equitable relief’ and also supported findings of ‘wilful blindness’ on the part of the lender’s solicitor, which satisfied equitable doctrine.

Click here for a Systems Intentionality analysis of ‘unconscionable system of conduct’ cases.

Example 9: pain(ful) relief

- Branding strategies by Nurofen and Voltaren for ‘targeted’ pain relief products

- But the targeted and generic products had identical active components. Same products, very different prices…

- These were very long-running campaigns

- Misconduct continued despite Shonky award and other complaints

Innocent error, carelessness… or just plain deceptive? Click here for a Systems Intentionality analysis.

Example 10: ‘Choice Architecture’ in website design

SI suggests that ‘default settings’ in automated and algorithmic settings loudly declare corporate values, priorities and intentions:

- Suppose a business earns profits from harvesting and selling its customers’ information obtained through an online app.

- Customers can protect their privacy by setting ‘location tracking’ defaults to ‘off’.

- Customers can easily find one setting: it is already set to ‘off – protect privacy’.

- Another default setting is much more difficult to find. It is set to ‘on – harvest data’

What does this suggest about the corporation’s values, priorities and intentions? Click here for a Systems Intentionality analysis.

Is its conduct misleading, and if so, is it reckless, or intentional? Click here for a Systems Intentionality analysis.

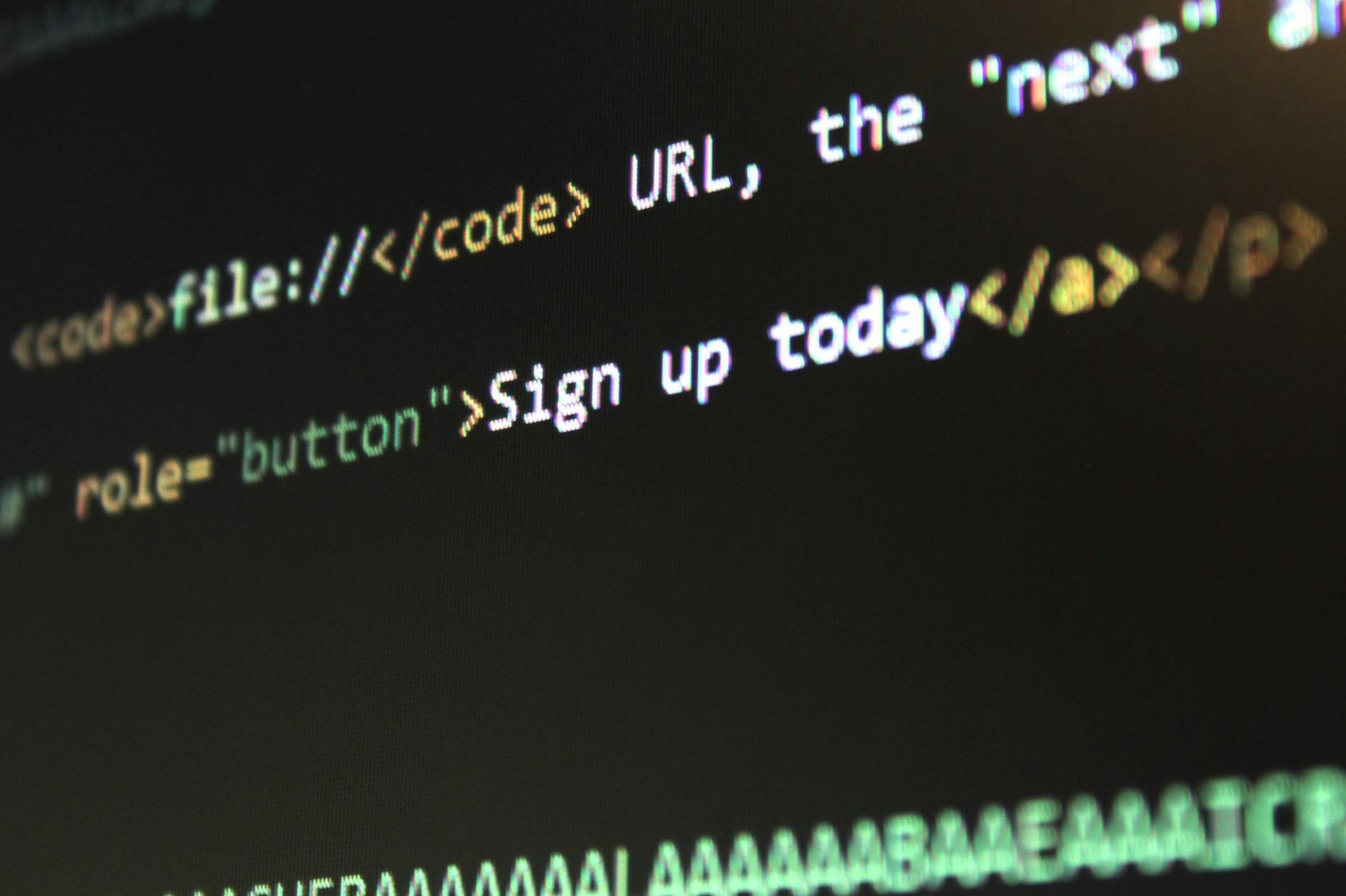

Example 11: Subscription (mal)practices

So easy to sign up!

Not so easy to ‘unsubscribe’…

What does comparison between the ‘subscribe’ and ‘unsubscribe’ processes say about the corporate mindset? Click here for a Systems Intentionality analysis.

Image credit: CPRC-Duped-by-Design-Final-Report-June-2022, via https://cprc.org.au/report/duped-by-design-manipulative-online-design-dark-patterns-in-australia/

Example 12: Artificial intelligence systems

Machine learning systems present a real challenge to ‘Where’s Wally’ approaches. ML systems are:

- Designing other systems

- Harvesting and experimenting at scale

- Unpredictable?

- Defy human analysis?

- ‘The robot did it!’

But deploying an uncontrolled, unaudited and unresponsive system is itself a choice… Click here and here for a Systems Intentionality analysis.